History of Real Tennis

A Detailed History of Real Tennis

Scholars tell us that hand-ball (jeu de paume in French) was played by the Greeks and the Romans, and by even earlier civilisations. There are references in the classics to a game that was played in a stone court, as is fives in our country today. Pilare, in Latin, was to play ball and pila was the word for a ball. Hence, palla in Latin and pelote in French.

The Roman legionaries, moving into Gaul, perhaps brought the custom of hand-ball with them. What is certain is that the game came to be played against the walls of town buildings and keeps of castles, and in and outside monasteries and ecclesiastical buildings. At a time when England held vast territories in France, the game was not slow to spread to our island. Indeed, the origin of the word tennis is thought to stem from the Anglo-Norman imperative tenetz! The cry of warning given by the server, “Take this! Play!”

Though tennis is traditionally styled the Game of Kings early records show that it was the ecclesiastical high-ups who first put their stamp of approval on the game. Prelates, Abbots and minor clergy played it with almost religious fervour. In certain provincial towns in France, the bishop of the diocese received a tithe of tennis balls on Easter Day. With choristers and schoolboys, the sport became a veritable craze and was frequently cited as a cause of truancy. The monastic type of building clearly lent itself to wall games, and it is thought that the eteufs or tennis balls were made from the discarded robes of monks.

During the Middle Ages, players began to protect their hands with a leather glove. Later this glove was to acquire gut strings in the style of a guitar. As this somewhat imperfect instrument evolved, a short six-inch handle came to be added to it. Early drawings depict this battoir and indicate that it was covered with vellum, a practice which led to the stealing of manuscripts by unscrupulous persons. A scholarly performer was once aghast to observe that his hired battoir was covered with still faintly decipherable fragments of a lost decade of Livy.

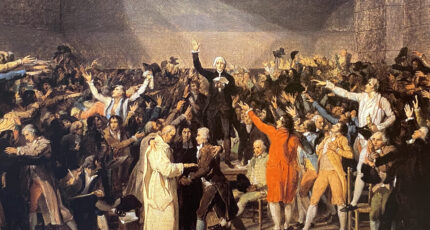

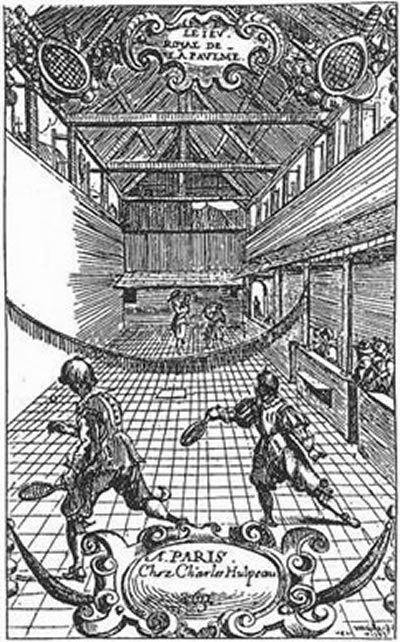

Throughout the history of the game great stress is laid on its therapeutic value. The Greek doctor Galen recommended it as the most salutary of all exercise. The first rules of tennis ever published- Hulpeau’s Ordonnance du Royal et honourable Jeu de la Paulme, Paris, 1592, began ”You gentlemen who desire to strive with another at tennis must play for the recreation of the body and the delectation of the mind, and must not indulge in swearing or in blasphemy against the name of God”. Pepys, in a diary entry of April 4th, 1668, writes, “…how my Lord of Pembroke says he hath heard the Quaker at the tennis-court swear to himself when he loses”.

The Maitre-Paumiers (aka the Original Real Tennis Professionals)

It is an incredible but documented fact that between 1550 and 1700 there were no fewer than two hundred and fifty courts of various shapes and sizes in Paris alone.

Small wonder that Shakespeare refers to” all the courts of France”, since many of her provincial towns could boast half a dozen or more of them. It was not until the fashion-ridden reign of Louis XIV that courts began to fall into disuse, because he, and therefore his courtiers, preferred to use the game as a medium for the laying of extravagant bets rather than playing themselves. This did at least encourage exhibition matches between the leading professionals, the maitres-paumiers of the day.

As the kings and many nobles employed their own professionals, the status of these men was considerable. In France,they had their own guild with appropriate escutcheon, shared admittedly in early days with the makers of bootand clothes-brushes, and they were protected by royal patent from unauthorised vendors of tennis balls and rackets. Statutes exist which set out minutely the duties and obligations of the maitre-paumier, as it was considered important to prevent the tennis-courts from harbouring undesirable elements of society. The paumier-apprentice had to learn the difficult art of making racquets and balls, special tools and equipment being required for the job. Before being admitted to his guild, the apprentice was called upon to give proof of his skills, not only as an artisan, but also as a player.

It would seem that the paumier had to employ a considerable staff of assistants known as marqueurs. They called the chases, marked up the games and sets, cleaned the court and rubbed the players down after their game.

With grateful thanks to Sir Richard Hamilton

Evolution of Tennis in the British Isles

Real Tennis Through the Centuries

All sorts of games with balls of various shapes and sizes have been played for centuries, originally as handball. But tennis – or Real Tennis as it is now more generally known – dates back to the 13th Century.

13th Century

The first reference to Tennis being played (with the hand) in the British Isles was during the reign of Alexander III in Scotland (1249-86).

14th Century

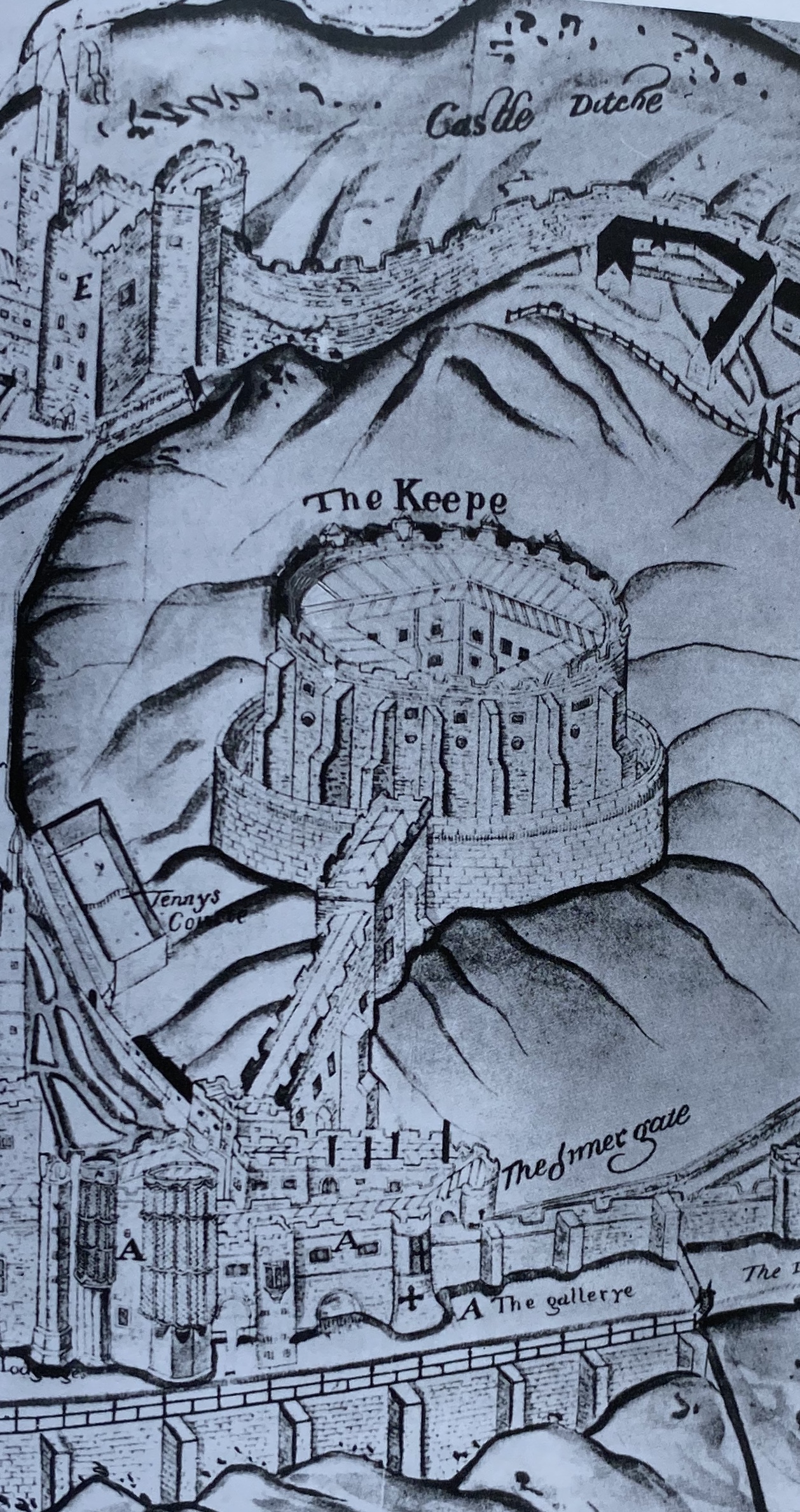

Edward III’s son built a court at Dublin Castle in 1361.

15th Century

Around 50 courts built, including the first purpose-built enclosed court. Courts in Scotland linked to James I (Perth), James II (Aberdeen) and James IV (Stirling Castle).

First mention of court next to Ironmongers’ Hall in Fenchurch Street and open masonry court at Winchester Palace in Southwark. Henry VII built courts at the Palace of Westminster, at Windsor Castle, Richmond Palace, Kenilworth Castle and Greenwich Palace as well as courts at Woodstock, Woking and Wycombe. First mention of a court in Oxford, probably attached to an inn.

16th Century

Over 100 courts built. Cardinal Wolsey built the first court at Hampton Court Palace and Henry VIII built a new court there modelled on the large covered court at Whitehall Palace; Henry VIII also built courts at Bridewell Palace and possibly at Petworth House.

James V built courts at Holyrood House and Falkland Palace in Scotland (photo shown). The Dukes of Norfolk built courts at Norwich Castle, Kenninghall and Charterhouse in London. The court at St Lawrence Pountney in the City of London was attached to an inn. Other courts were built in both Oxford and Cambridge.

17th Century

About 75 courts built, with Royal new or replacement courts built at Somerset House, Newmarket Palace, Richmond Palace, St James’s Place, Holyrood House and Hampton Court Palace (photo shown).

Many courts built in London, mostly attached to inns. After the Civil War, the Puritans frowned on Tennis but on the Restoration of the Monarchy, Charles II built a new court at Whitehall and a replacement court at Windsor Castle. The first and second courts in James Street, Haymarket, were built.

18th Century

70 courts built. Many courts built around the British Isles, in Bath, Birmingham, Bristol and Liverpool, as well as in London. (Oxford University shown in photo.)

Courts built at Goodwood House and, encouraged by Royal patronage, at Langley Park, Woburn Abbey, Crawley Court and Brighton Pavilion. Court (said to be the best in Europe) built on Lazer’s Hill in Dublin (paid for by subscription so could qualify as first Tennis club); many other courts built in Dublin, mainly attached to taverns.

19th Century

Over 125 courts built throughout the country, with many still standing and in operation:

Hatfield House (1842) [shown in photo], Leamington (1846), Cambridge (1866 and 1890), Petworth House (1872), Canford (1879), Manchester (1880), Bridport (1885), Queen’s (1887), Holyport (1889) and Jesmond Dene (1894). In 1856, the Prince’s Club opened in Hans Place, Knightsbridge, with five Rackets courts and added a Tennis court in 1860; this venture failed but was replaced by a new club with two Tennis courts in 1889. On the closure of the James Street court in 1866, the headquarters of Tennis shifted to Lord’s before moving to the new Prince’s Club.

20th Century

The court building programme from the late 19th Century continued, with new or replacement courts at Lord’s (1900), Newmarket (1901), Moreton Morrell (1905), Hardwick (1907), Seacourt (1911) and a few others which have not survived.

The Tennis & Rackets Association was formed in 1907 and was initially based at the Prince’s Club, Knightsbridge. During the First World War only Prince’s, Queen’s, Lord’s, Manchester and Brighton remained open. It was very difficult to recover from the War and, with Spanish Flu and the Great Depression, further courts were lost between the wars although the Lambay Island court in Ireland was opened in 1922. During the Second World War, only Lord’s and Manchester remained open whilst the Prince’s Club and Brighton, amongst others, were lost. The T&RA moved to Queen’s and, after the war, the slow process of recovery began. All the current courts were re-opened and, in 1990, a golden decade began with the opening of The Oratory court, followed by the Harbour Club, Bristol, Prested Hall (2 courts) and Middlesex, and the restoration of the court at The Hyde.

21st Century

Two new courts built to date, both at independent schools – Radley and Wellington (pictured).

David Best/RAD, October 2019